Joe Jajati, a Syrian Jew living in New York, described his grandfather’s life in Syria as being even greater than the American Dream.

“My grandfather was born into a poor family, and 20 or 30 years later, he had what in America we would call the American Dream, but he built it in Damascus as a Jewish man,” Jajati said.

That “Syrian Dream” materialized in the heart of Damascus under the name “The Grand Store," or “Al-Makhzan Al-Kabeer” as it was known in Arabic, which was once one of Damascus’s most renowned clothing shops that Jajati’s grandfather owned. Decades later, the Jajati family name has become iconic in Damascus, often recognized when he visits Syria. Jajati, born in Damascus in the early 1990s, now dreams of opening his kosher kitchen in Damascus to help revive Jewish life in Syria. His goal is to create a welcoming and safe space for Jewish visitors, encouraging them to reconnect with their roots in Syria and possibly return.

“I am not doing it for business,” Jajati said. “I am doing it for Syria."

Syria had a strong economy until 2011, when protests demanding freedom escalated into a brutal civil war in Syria, resulting in devastating humanitarian consequences. Over 13 million people were displaced, and more than 600,000 people were killed. After fourteen years of war, President Bashar Al-Assad fled to Moscow, bringing an end to the violence and the Assad regime.

Today, as Syria opens its doors to the world, a question is being whispered among Syrian Jews in the diaspora: Can they return to their homes? Some Syrian Jews have answered this question by taking the risk of returning after thirty years. In recent months, a small delegation of Syrian-American Jews returned to Damascus, where they visited the old Jewish Quarter and prayed in the Faranj Synagogue for the first time since the 1990s.

As we worked on this article, we noticed how Syrian Jews in the diaspora become deeply emotional when they talk about Syria. Nattan, who left Damascus more than 30 years ago, was in the middle of describing his childhood in Syria when he stopped and said: “You are opening my wounds by talking about Syria.” Although Nattan has not returned to Syria since he left, he still carries his Syrian passport and calls himself a proud Syrian Arab.

While we had hoped to write this piece in Syria, to be on the ground and deliver a closer picture of the situation there, this was not possible due to Alaa's refugee status in Jordan. As a Syrian currently living in Jordan, he cannot return to Jordan if he decides to visit Syria. This is the case for most Syrian refugees here; many want to visit Syria but are not ready for a permanent return.

Despite these limitations, we decided to work on this article to deepen our understanding of Syrian Jews and to help educate others about their history, culture, and heritage. We also wanted to hear directly from Syrian Jews about their hopes and vision for Syria moving forward. While historical records can provide a distant reading, we spoke with those who experienced it to provide a more profound picture of the Syrian Jewish community.

The history of Jews in Syria

The history of Jews in Syria dates back long before Syria was part of any empire, to when it was divided into many states, kingdoms, and tribal territories. Some of the earliest Jewish connections to Syria date back over 3,000 years, and according to many biblical stories, the first Jewish presence in Syria was during King David’s rule in 1000 BCE, when he conquered Aram (Northern Syria) and Aram Zobah (Aleppo), as mentioned in the Bible. From the time of King David, Syria underwent many changes of power, which included the Arameans, Greeks, and eventually the Romans in 64 BCE.

By then, Jewish communities had established themselves across Syria. Many Jews had arrived from Israel and Judah because of exile, trade, or military service. Under each empire, Jews adapted and remained present. They thrived under the stability and protection of Roman law, with some Jews even receiving Roman citizenship. But these privileges did not last long, as Jews in Judea were under tighter control by the Romans, resulting in many Jewish revolts leading to Jewish-Roman wars in Judea, which deeply affected the demographic of the region. Many Jews fled to nearby regions looking for safety, which led to the growth of the Jewish population in Syria.

Since then, many empires have ruled in Syria, starting from the Byzantine Empire, which was the continuation of the Roman Empire in the East in the 4th century. For almost 300 years, Jews were forbidden from entering Jerusalem by the Byzantines, which resulted in a constant tension between Jews and Christians in the area. John Chrysostom, a prominent Church Father, played a central role in shaping the Byzantines’ hostility towards the Jews, portraying them as heretics and "Christ-killers" in his sermons. This conflicted with the Latin Christian tradition, influenced by Augustine of Hippo, which viewed Jews as misguided but necessary for Christian history. However, some scholars argue that Augustine's views still contributed to anti-Semitism in Christianity.

After centuries of persecution under the Byzantine Empire, the situation shifted when Muslim forces defeated the Byzantines in the Battle of Yarmouk, leading to the Muslim conquest of Syria in the 7th century. Under Islamic rule, Jews were allowed to return to Jerusalem and practice their faith freely. Jews were also recognized as people of the book and given protected status, although they had to pay a special tax designated for non-Muslims, known as jizya. Islamic caliphates continued to rule Syria up until the 20th century, including the Umayyad Caliphate, the Ayyubid Dynasty founded by Salah Al-Din, and the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Under each Islamic Caliphate, Jews were treated differently but generally better than in Europe at the time.

The region faced many invasions and wars during Islamic rule, such as the Crusades and the later Mongol invasions. The Crusades caused widespread instability in the Levant, as their primary goal was to capture Jerusalem and the Christian holy places from Muslim rule. Whereas some of the Jewish communities within Palestine experienced immediate persecution and massive taxation from the Crusaders, most Jews sought refuge in the largely Muslim-controlled Syria.

The influx of Jews into Syria increased rapidly in 1492, when Sephardic refugees fled from the Spanish Inquisition and arrived on Syrian shores. These Spanish families soon became Aleppo’s chief rabbis, scholars, and community leaders. In homes across Aleppo and Damascus, one began to hear Judeo-Spanish and Judeo-Arabic alongside the old synagogue chants. This blending of ancient local tradition and Sephardic fervor would define Syrian Jewry for centuries to come.

During this period, Syria was a haven not only for Jews but for their books, Torah scrolls, relics, and amulets. For example, the Aleppo Codex, one of the oldest and most accurate versions of the Old Testament, created in Tiberias, was later moved to Aleppo, Syria, where it remained for centuries. The codex was kept in the city’s central synagogue as a treasured religious and cultural symbol. Although it was damaged during anti-Jewish riots in 1947, the codex was later smuggled to Israel due to instability in Syria.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Jews were still second-class citizens, and their lives varied between times of protection and times of discrimination and persecution. Despite that, they were still able to establish themselves as a resilient community in Syria and work in industries like commerce, with few pogroms or restrictions. While many Jews were forced to convert to Islam, they still enjoyed more religious freedom than in most of Europe pre-emancipation.

Life for Syrian Jews began to get significantly worse during the European colonization of the Levant region. Under the 1920 French Mandate for Syria, Syrian Jews faced increasing restrictions and persecution, which ultimately led to their emigration. Initially, Jews were recognized as an integral part of Syrian society. However, the creation of Israel sparked a rise in anti-Jewish sentiment, which led to pogroms, restrictions on travel and emigration, and economic marginalization, especially with the rise of the Syrian nationalist movement.

Driven by Ashkenazi Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the rise of Zionism led to waves of Jewish immigration to Palestine and the formation of a nationalist settler project aimed at establishing a Jewish homeland. While Zionism was a response to persecution in Europe, its implementation in Palestine resulted in the displacement and marginalization of the Palestinian Arab population.

The Zionist movement negatively affected the lives of local Jewish communities who had coexisted with their Arab neighbors for centuries and were often culturally integrated into the region. As tensions escalated, Jews in Arab countries faced violence and pressure to emigrate, while Palestinians were persecuted by Zionists. Thus, both local Jews and Palestinians became victims of a political project shaped by colonialism.

By the 1930s, the Syrian government had started cutting off Jews' freedom, who at this time numbered roughly 40,000. They experienced extreme economic hardship, with Jewish bank accounts frozen and Jewish members of the government dismissed. Jews were severely restricted in their freedom of movement and were not allowed to acquire a driver's license or to leave the country freely. Syrian Jews were under constant surveillance by the secret service, Al-Mukhabarat, and those who wanted to leave were forced to escape. Anyone who was caught faced forced labor or even death.

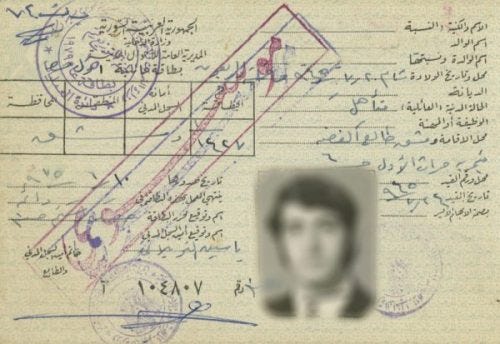

Syrian Jews were even identified in state documents by the word “Mousawi”, a name derived from the name of the prophet Moses. Even though Syria was home to many religions and sects, Jews were the only religious group singled out in official government papers, which was largely prompted by the establishment of Israel in 1948.

Nattan, a Syrian Jew born in the early 1970s, mentioned that the “Mousawi” law didn’t significantly affect his daily life because most Syrians were equally oppressed under Assad’s dictatorship, regardless of religion. Despite that, this policy was a form of discrimination that isolated Jews as a distinct and suspect population, similar to the yellow badges that Jews were made to wear in Nazi Germany. Such policies helped justify broader repression and contributed to the narrative that Jews could not belong in Arab society.

Despite all these limitations inherited under the Assad regime, Nattan mentioned that before Hafez Al-Assad came to power, the Jews were much more targeted and persecuted. Nattan recalled a traumatic incident where a grenade was thrown into a synagogue in Damascus, causing his father to lose his legs. The 1949 Menarsha synagogue bombing, the event where Nattan’s father lost his legs, took place on August 5th, 1949, in the Jewish quarter of Damascus, Syria. The grenade attack claimed the lives of 12 civilians and injured about 30. Most of the victims were children. This attack happened at the same time when Syria and other frontline Arab states were conducting armistice talks with Israel in Switzerland. A simultaneous attack was also carried out at the Great Synagogue in Aleppo.

Despite many Syrian Jews living under sanctions and violence, the government tried to paint a different picture of reality. In 1991, Syrian state TV aired a one-hour propaganda video in English that featured interviews with local Jews to portray a peaceful coexistence within Syria. In a surreal moment, Rabbi Hamra claimed that Jews were celebrating two festivals that Monday: a traditional Jewish holiday and the reelection of President Hafez al-Assad, a claim that had little basis in reality.

On the contrary, Syrian Jews suffered under Hafez Al-Assad and were even banned from leaving the country, which led to international pressure, particularly from the United States under H.W. Bush. This resulted in Hafez Al-Assad agreeing to lift the travel ban on Jewish emigration from Syria in 1992. Syria’s Jews immediately started leaving for the United States, which offered them political asylum. The U.S. embassy in Damascus arranged for visas, and the Council for the Rescue of Syrian Jews organized their travel to New York. Nattan was among the Syrians who took advantage of the U.S.'s new open policy. Though he had left Syria at twenty years old in search of a better financial future, he felt that the U.S. deceived him when he arrived.

“I was promised to be given a house and a job in New York, but when I arrived there, the house was a 25-year loan that I had to pay, something that was not told to me before I left,” Nattan said. “I regret leaving Syria. I was not forced to leave, but the promises that were made to us were the reason I decided to move to the States. After I arrived, I couldn't live in the U.S. as a traditional Arab man. I wanted to go back to the Middle East, and when I knew Syria wasn't an option, I came to Israel.”

Nattan described the Syria that he had left behind as simple and peaceful during his childhood. He recalled a time when Muslims, Christians, and Jews lived together in close proximity. The groups often poked fun at each other playfully; for example, Damascene Jews created a dish called "Muslim Harban" (meaning “The Muslim Who Ran Away") as a humorous way to share meals with their Muslim neighbors during Jewish holidays. When Muslims in Damascus learned the recipe from them, they named it "The Traveling Jew" (Yahudi Musafir). It was all in good fun, reflecting the coexistence between Syrians of different religious sects.

“When my mother got sick and could not cook for us, my Palestinian neighbors would come every day bringing food, making sure my mom and I were well fed and being taken care of,” Nattan recalled.

While most Syrian Jews left by 1994, not all decided to leave. The Jajati family refused to leave their shop and house, deciding to stay in Syria until they sold their shop in 2001.

“By 2001, everyone was gone, and there was no way for someone to be able to live as a Jew anymore — not because you're not allowed, but because there were no other Jewish families. There were no more rabbis to slaughter animals for [Kosher] food, no one to do the circumcision for kids, no Jewish families to marry from. So all these things basically forced people who stayed till the end to leave,” Jajati explained.

While these testimonies show a different image of what was being painted in the Western media about Arabs, especially Muslims' treatment of Jews, there are still people who were forced to leave Syria because of persecution. These experiences varied largely because of social and economic status, as wealthier families were less likely to be affected by persecution or limitations by the government. Many Syrian Jews, like Nattan’s and Jajati’s families, were fortunate to have a voluntary departure. According to Jajati, this is why Syrian Jews are the only Arab Jews who are still connected to their home country.

Syrian Jews’ conflict of identity

While Jajati and Nattan have different stories, they both agreed that the modern Jewish culture is a result of European colonialism and feels distant from traditional Judaism. Nattan’s decision to go to Israel was based on his desire to live in the Middle East, with Syria not being an option at that time. Nattan faced many cultural shocks in Israel, describing it as European culture.

“As a traditional Arab man, this culture does not represent me,” Nattan said. “It is a European culture.”

Language and cultural differences made integration difficult for many Arab Jews. According to Nattan, Syrian Jews in Israel often experience an identity crisis, torn between their Arab roots and European colonial culture that dominates Israel.

“If I have the chance to go back to Syria, I would go back immediately,” Nattan added. “But my Israeli passport prevents my entry there.”

Jajati had a similar feeling, but his experience was different in its own way.

“I went to a Jewish school in New York, all the kids had peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on rye bread, and I showed up with pita and labneh,” Jajati said. “Even though it's a small thing, all these little differences made me feel more connected to my Syrian roots.”

Both Jajati’s and Nattan’s stories reflect the deep cultural gap many Arab Jews felt when they left their homes. Most Syrian Jews emigrated to the United States, especially to Brooklyn, while others went to France, Canada, or Latin America. Many eventually made their way to Israel, using these countries as just a temporary home. Fewer than a hundred Jews were estimated to remain in Syria, mostly elderly individuals who chose not to leave. The once-thriving Jewish life in Damascus and Aleppo had almost entirely disappeared. Synagogues, cemeteries, and homes were often abandoned or fell into disrepair, though some have been preserved.

By 2011, fewer than 20 Jews were estimated to still live in Syria, the majority of them in the Jewish Quarter of Old Damascus. As of 2025, Syria had approximately 71 documented Jewish heritage sites, including synagogues, cemeteries, schools, and other communal buildings. Of these, at least 32 have been destroyed or have deteriorated beyond repair, primarily due to neglect, conflict, and looting during the Syrian Civil War. Syrian Jews, who already have a fractured identity from being Arab and Jewish, had their roots torn down even more by the war. Syria's rebirth with the new regime might give Syrian Jews the chance to restore the few symbols of Jewish heritage they'd lost from their homeland.

The Jewish return to Syria

Today, Syria has the chance to reclaim its former status as a haven for Jews around the world. As we were writing this article, we asked ourselves this question: What would it mean if Syrian Jews returned? Would it upend the long-standing Zionist claim that Jews can never be safe amongst Arabs? If Syria can build a space where Syrian Jews feel welcome again, will it challenge decades of colonial narratives that justified the Israeli settlements at the expense of Palestinians?

While we do not have answers now, it might take us decades to get there with many serious obstacles remaining. Many physical symbols of Jewish heritage, including synagogues, cemeteries, and homes, have decayed or been repurposed. Sectarian divides amongst Syrian Jews are also a barrier to rebuilding.

"Everyone wants to be in charge of the sites, and this is making it difficult for us to unite,” Jajati said.

Additionally, for those with Israeli passports like Nattan, returning remains a legal and political obstacle. Furthermore, Israeli airstrikes have not stopped in Syria even though the Assad regime has fallen.

“When Israel strikes Syria, it doesn’t matter who the targets are or what politics are behind it; it makes me sad because it’s happening in my homeland,” Jajati said. “I want peace, not because I support Israel, but because I want peace for my country, Syria.”

Despite these challenges, there are small but meaningful signs of hope. The return of a historic Torah to the Faranj synagogue or Jewish prayers being heard again in Damascus are historic events that could be the beginning of a new era, building on what Jajati’s grandfather once called “the Syrian dream.” Now, decades later, his grandson is imagining what it would mean to see that dream reborn. Whether through investments like starting a kosher kitchen or regular visits to Jewish sites in Syria, Syrian Jews are slowly reconnecting with a homeland they never truly forgot.

“While I understand that some have different ideologies, I strongly believe that war is awful and should end. Even if I can’t go back, I want to see a safe Syria, for all its people,” Nattan says. “I am not sure if I can go back again, but my dream is to be buried in Damascus, next to my family.”

View our sources for this piece here.

So many cultural complexities in the Middle East! I did not know any of this history, so thank you for enlightening me.