Horrified, Colonel Byrd prodded open the door to the sweat-box dungeon.

A foul stench filled the air. Bits of cornbread littered the floor. The room was sealed completely, leaving its inhabitants to suffocate as the oppressive Georgia sun cooked its walls. Byrd finally met the gaze of the black man who lay helplessly on the ground. Exhausted and ragged with illness, the man, whose name was not recorded, only asked Byrd if he could have a sip of water. The year was almost 1900, thirty-five years after the United States government abolished slavery.

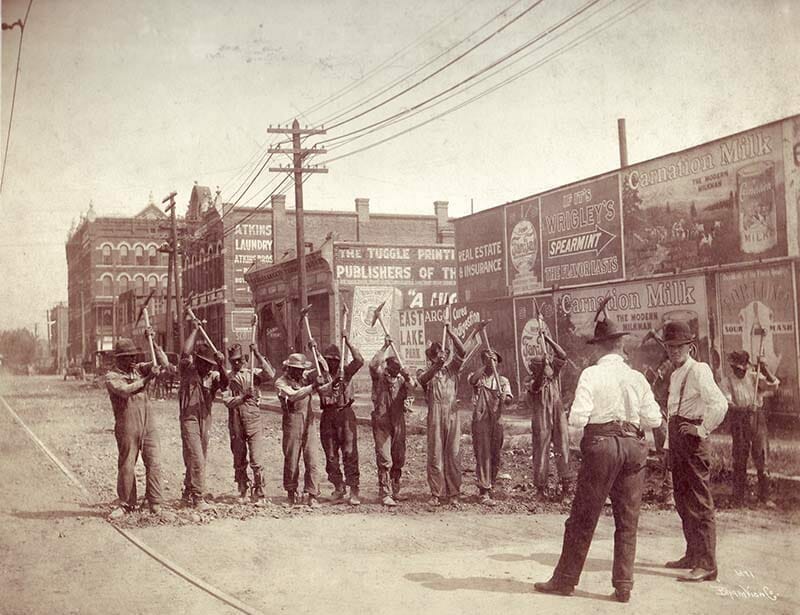

Although the Thirteenth Amendment emancipated millions of enslaved African-Americans, it left open a loophole that allowed criminals to be subjected to involuntary servitude. For the South, whose economy and infrastructure were in ruins after the Civil War, this exception became a perfect substitute for chattel slavery. Laws were quickly passed across the South to convict black people of petty crimes, known as Black Codes. Once convicted, they were leased out to employers such as planters and manufacturers. The South had reinvented slavery — but this time, it went by the name of “convict leasing”.

A colonel from Georgia named Philip Byrd set out to document the conditions of convict laborers. Byrd immediately discovered horrors beyond imagination. He encountered scarred women who had endured whippings and old men who had been beaten to death. Workers were given rotten food after working up to twenty hours a day. Upon visiting the “sweat-box dungeon” at a labor camp in Wilkes County, Georgia, Byrd remarked:

How human beings could consign a fellow being to such an existence, I cannot understand any more than I can understand how a human being could survive a night of confinement in such a den.

Because convicts were rented, they were effectively disposable. This made them prone to even worse treatment. According to civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell, in 1907:

In some respects, the convict lease system, as it is operated in the States where it is in vogue, is much less humane than was the bondage endured by the slaves fifty years ago. For, under the old regime, it was to the master’s interest to clothe and shelter and feeds his slaves properly, even if he were not moved to do so by considerations of mercy and humanity, because the death of a slave meant an actual loss in dollars and cents, whereas the death of a peon today involves no loss whatsoever either to the lessee or to the State.

The brutal continuation of forced servitude is a frequently overlooked portion of American history. Like many others, I viewed slavery as a relic of the distant past, but while doing the research for this article, I came across accounts of isolated African-Americans in the Deep South who had not received their freedom until the 1960s. By asking why this history only recently surfaced, we can learn a great deal about the individuals responsible for keeping slavery alive after its abolition.

A forgotten history

For more than a century, thousands of records detailing forced black labor after the Civil War were largely inaccessible. This is partly because the officials who archived these records were the same people who brought new systems of exploitation to fruition.

Douglas A. Blackmon, author of Slavery by Another Name, notes how this obfuscation tainted the perspectives of historians today. Prior to the release of his book, many academics agreed that the history of convict leasing couldn’t be determined because “so few of the original records of the arrests and contracts under which black men were imprisoned and sold had survived”. Blackmon opted to gather these records himself by visiting courthouses throughout the South, and in doing so, he reached a different conclusion:

As I moved from one county courthouse to the next in Alabama, Georgia, and Florida, I concluded that such assumptions were fundamentally flawed. That was a version of history reliant on a narrow range of official summaries and gubernatorial archives created and archived by the most dubious sources — southern whites who engineered and most directly profited from the system.

Through a meticulous hunt for evidence, Blackmon was able to paint a stunning picture of slavery’s continued legacy. He makes it clear how public servants, normally in charge of administering justice, played a key role in re-enslaving freed black people.

“Sentences were handed down by provincial judges, local mayors, and justices of the peace,” said Blackmon. “[They were] often men in the employ of the white business owners who relied on the forced labor produced by the judgements.”

Their strategy was massively successful. By 1898, almost three-quarters of Alabama’s state revenue came from convict leasing. It took another three decades for the state to finally outlaw the practice. However, convict leasing was only one of several iterations of slavery that continued after the Civil War.

Debt bondage was another, in which black people — many of whom were sharecroppers — were forced to work until they had repaid a debt to their employer. Many times, employers refused to acknowledge that their debt had been paid, thus keeping the victims bound as laborers. If workers left before their debt had been settled, they could be arrested, threatened, beaten, or killed.

This is how Mae Louise Miller, a black woman from Mississippi, was enslaved until 1961. Miller’s family became indebted to a plantation owner before she was born. For twenty years, she was forced to harvest cotton, corn, peas, and other crops while being physically abused by the family who held her. Miller was not aware that debt slavery was illegal — according to her, “I thought everybody was living that way”. In 2003, she and her six siblings joined a lawsuit demanding reparations from several private institutions that historically aided the practice of slavery. The lawsuit was later dropped.

It is evident how the seeds of American slavery, sowed in the early 1600s, blossomed after the Civil War instead of dying out. Each of its branches left trauma and destitution in its wake, setting millions of African-American families back by decades, if not more.

Slavery in the modern era

Although slavery has largely come to an end in the United States, it still persists on a smaller scale. In 2021, the U.S. government investigated a human trafficking ring where over a hundred migrant workers were forced to dig for onions at gunpoint. Trapped by electrified fences, the victims had no easy way out.

Overseas, debt slavery is still common in countries like China, India, and Pakistan. India alone harbors over 11 million people trapped in bonded labor. The government abolished it in 1976, but it remains prevalent due to poor enforcement. Kiran Kamal Prasad, who founded Jeevika, an organization dedicated to eradicating bonded labor, hypothesized as to why this is the case.

“Very often, the authorities are not implementing the act,” said Prasad, in a video. “Maybe the majority of the authorities come from the same communities as the keepers of bonded laborers. They could be of the same dominant castes as the landlords.”

If this is the case, it mirrors how state officials in the American South allowed convict leasing to continue despite the terrible conditions workers faced. Activists like Prasad have been instrumental in helping those trapped in debt slavery. Roughly 30,000 people have been freed because of Jeevika.

While bonded labor may never be completely eradicated, its demise rests upon the tenacity of everyday citizens, whether grassroots organizers or historians. The stories of victims such as Mae Louise Miller are a reminder that no matter how tight the yoke of slavery, the human will remains stronger.

View our sources for this piece here.

We like to think such systems no longer exists, but having lived in the Middle East for decades and traveled widely, the truth is something different. So-called “contracted workers” are brought in, and bought, sold and traded with impunity in what is surely at least a remnant of slavery. Another great piece. And thanks for the book recommendation.

Thank you for shedding light on this horrific practice. This is the first I've heard of it.