Northwest Philadelphia, August 25th — Standing about twenty feet away, local cat trapper Hilary Coulter watched carefully as the petite head of a tuxedo kitten poked curiously inside the metal trap she had set out.

“Don’t go any closer, or you might scare him away,” she told me.

The kitten pawed hesitantly at the newspaper-lined mesh, but the tuna at the opposite end of the cage proved to be too enticing. It stepped inside. It had been almost half an hour since Coulter had set up the trap, but her patience finally paid off. The trap sprung.

Time had been running out for Coulter to catch the kittens in this colony, as they were nearing the age at which they could not be socialized anymore. Cats who are not acclimated to human contact are forced to spend the remainder of their lives outdoors without the care of a permanent owner. On the street, these cats can suffer from abuse, diseases, and other hazards such as freezing temperatures or sweltering heat waves. In addition, they can threaten local wildlife such as some endangered species of birds.

This colony of cats in Northwest Philadelphia is just one of hundreds throughout the city — which provides a glimpse into the widespread issue of stray and feral cat populations spiraling out of control in densely populated areas. According to Philadelphia’s Animal Care and Control Team (ACCT), roughly 400,000 stray and feral cats live outdoors. Trapped cats are usually taken to a veterinarian, where they are temporarily sedated, vaccinated, and cleaned before they are put up for adoption. However, this tuxedo kitten wasn’t old enough to undergo involved medical treatment.

“I just can’t see putting this cat under anesthesia because he’s so little,” said Coulter. “I’m more comfortable when they’re three pounds — a little bigger.”

Kittens in this situation can stay in a shelter until they’re ready to receive treatment, such as at the facilities of animal care organizations like The Cat Collaborative (TCC), where Coulter works as a volunteer outreach coordinator. To learn more about the stray cat problem and how these organizations work, we spent a day with volunteers from TCC. In addition to this article, we produced a mini-doc that you can watch below.

The history of stray cats

To understand why stray and feral cats became so prevalent in cities like Philadelphia, we can look at their history. Cats were domesticated as early as 10,000 years ago in the Middle East during the Neolithic Period, which was marked by the shift from the nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to more permanent agricultural communities. In addition to being social companions, cats served a practical purpose to humans by killing pests, which could harm grain production, for example.

Cats’ native claim to Mesopotamia explains why residents of cities like Istanbul not only tolerate, but actively embrace their massive stray cat population. Their prolonged existence likely enabled the local ecology to develop in such a way that cats no longer pose a threat to nearby wildlife, which is not the case in other parts of the world.

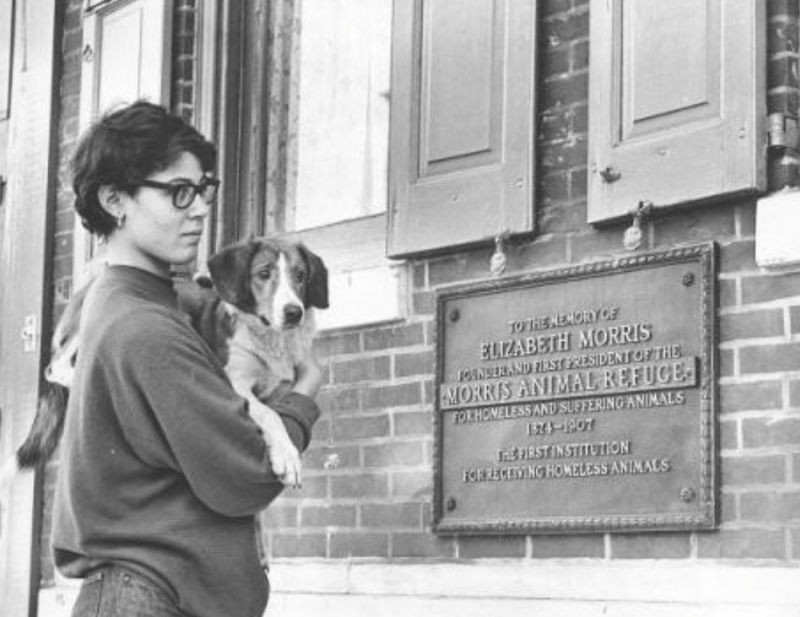

In places like Philadelphia, cats are a relatively new development. After clambering aboard the ships of early European colonialists, cats arrived in North America during the mid-1600s. As they quickly populated the East Coast, the number of strays in large cities drastically increased — a pattern that continues to persist. Interestingly, Philadelphia has a rich history of helping stray or otherwise neglected animals. For example, the Morris Animal Refuge was founded in 1874, which made it one of the first animal care organizations in the United States.

Fixing the stray cat problem

Local organizations such as The Cat Collaborative follow in the footsteps of early animal care groups, nowadays armed with more advanced methods of rescuing strays. TCC practices a method called TNR, which stands for trap, neuter, and return, release, or respond — depending on the organization. The goal of TNR is to get as many cats off of the street as possible while simultaneously slowing their population growth.

In practice, TNR groups can face a number of challenges, ranging from coordinating with cat caretakers across multiple communities to finding a permanent home for a cat once it’s been rescued. When all goes smoothly, TNR can greatly improve stray cats’ quality of life and reduce their population growth. However, the entire process is highly resource-intensive. Kathy Jordan, founder of animal care organizations Green Street Rescue and Le Cat Café, told us that her groups are losing money — spending up to $15,000 per month on operating costs.

“We’re all fighting so hard for the same thing,” said Julianne Davis, the outreach coordinator at TCC. “Everyone is a volunteer … they are taking every hour they have for cats. They really want the best outcome for the cats in Philly.”

However, TNR has sparked controversy amongst the scientific community and wildlife advocacy groups for being ineffective at a large scale due to the sheer rate at which cats reproduce. According to the American Bird Conservancy:

Rather than immediately reducing numbers through removal, TNR practitioners hope to slowly reduce populations over time. The scientific evidence regarding TNR clearly indicates that TNR programs are not an effective tool to reduce feral cat populations. Rather than slowly disappearing, studies have shown that feral cat colonies persist and may actually increase in size.

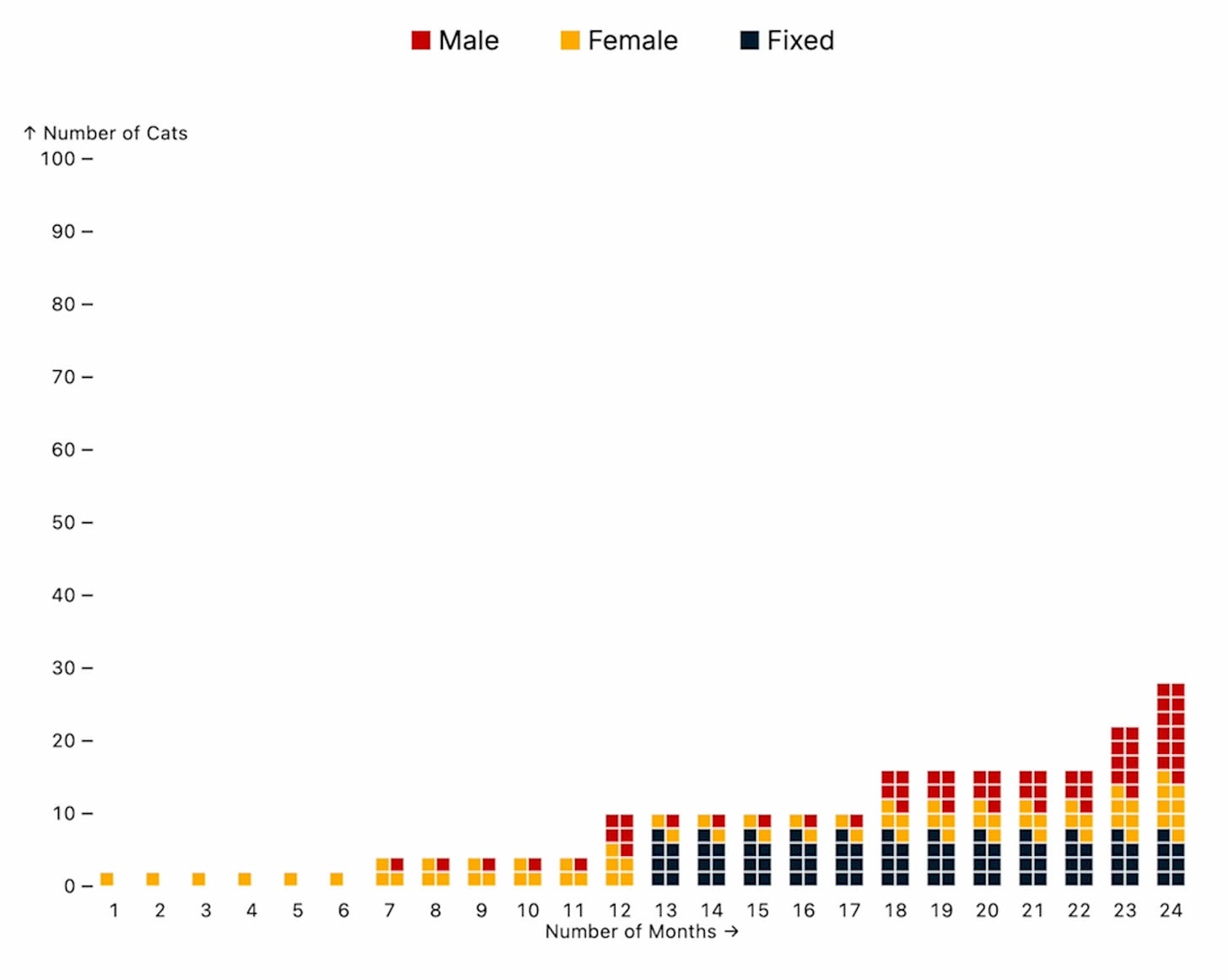

We can see this effect by simulating the growth of a cat colony and observing the effects of TNR at varying levels of coverage. In the graph below, we model the month-over-month growth of the colony, representing each animal with a square. Starting with just one pregnant female cat and no human intervention, the population can balloon to almost a hundred in only two years.

On the other hand, if three-quarters of cats are trapped and fixed one year into the existence of the colony, the population growth is greatly subdued — indicating a success for TNR.

However, the vast majority of cats must undergo TNR in order for it to be effective. According to a 2004 study, at least 75% of cats must be trapped and fixed in order for the population to be controlled. The figure below shows what could happen if only 20% of a cat colony undergoes TNR.

To date, The Cat Collaborative has rescued almost 14,000 cats in Philadelphia. Given that there are close to 400,000 stray cats in the region, it represents progress but indicates that there is still more work to be done. In addition to ramping up rescue efforts, multiple members of TCC stressed the importance of educating the general public about the stray cat problem in order to solve it.

“I wish people would recognize how infant-like these animals are, and how little able they are to take care of themselves,” said Paul Gerber, a cat trapper at TCC and former schoolteacher. “As successful as we are, we can’t solve the problem — we can only help the cats that we find. … If more members of the communities where the need was were pitching in, you might see a reversal of this.”

Special thanks to Teo Genera for contributing to this piece as a videographer. View our sources and further reading for this piece here.

How much do you know about the history of your cat. Free read.https://abforbes.substack.com/p/the-history-of-our-pet-cats?r=yn8c0

I guess it's right to "control" the cats but in my heart I root for the wild and free cats. I feel sorry for cats who end up in a little apartment staring longingly out the window, dreaming of freedom. If I was a cat I think I'd prefer being outside despite the hardships.