When I began reading Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. I imagined that I’d be met with somber, matter-of-fact descriptions of her daily life, each capped with a brief remark that offered a glimpse into her personality. Maybe she would detail her hopes of Allied liberation or her fears of being discovered, but I couldn’t think of much more than that.

Instead, I became acquainted with the mind of a witty, candid person who was articulate beyond her years, knew how to find the humor in every situation, and was remarkably self-aware and introspective at only thirteen. By the time I finished Anne’s diary, I understood why it had been read by more than thirty million people from around the world.

In one of her most memorable passages — written a year and a half before the end of World War II — she says:

For a long time I haven’t had any idea of what I was working for any more; the end of the war is so terribly far away, so unreal, like a fairy tale . . . I must work, so as not to be a fool, to get on, to become a journalist, because that’s what I want . . . I want to go on living even after my death!

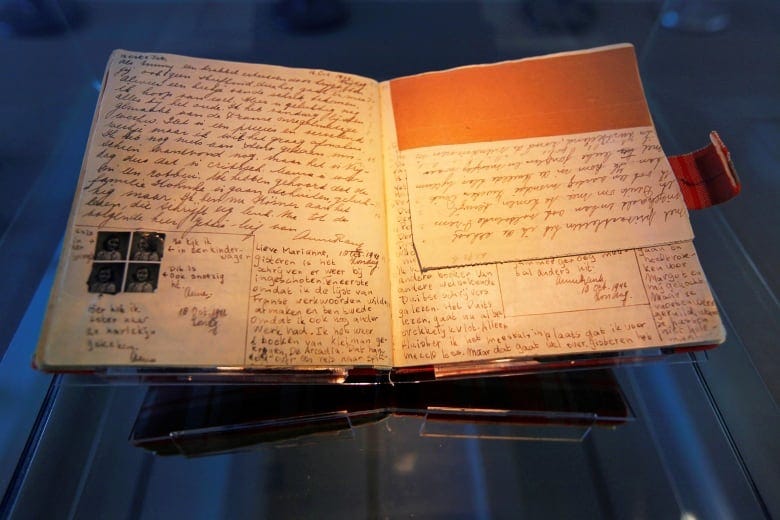

At first, it seems like a coincidence that Anne was able to achieve her dream of living after her death. In reality, her diary’s transformation from modest red-checkered notebook to critically acclaimed bestseller, play, and film was the product of a fierce legal battle between her father, Otto Frank, and Meyer Levin, a Jewish-American novelist whose obsession with dramatizing Anne’s story bordered on insanity.

In their fight to stage their own version of the diary, what started as a friendly collaboration ended mired in bitterness and spite. Their conflict raises difficult questions about who gets to recount history to the next generation, and more importantly, how history can become distorted as it becomes part of the mainstream media.

The red-checkered notebook

As the midday August sun glared down upon the streets of Amsterdam, a group of German police officers burst into the house where Anne Frank had remained hidden for over two years. The “Secret Annex”, as it was called, had sheltered the Frank and Van Pels families until their capture in 1944. Anne was sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp along with her sister, where she died in 1945.

She was fifteen years old.

Her father, Otto Frank, was the only surviving member of the Secret Annex. In the following years, Frank managed to recover his daughter’s diary and sell several thousand copies in Germany, France, and the Netherlands under the title Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annex).

From a 1952 review of Het Achterhuis published in the New York Times:

Because the diary was not written in retrospect, it contains the trembling life of every moment -- Anne Frank's voice becomes the voice of six million vanished Jewish souls . . . one feels the presence of this child-becoming-woman as warmly as though she was snuggled on a near-by sofa.

These were the words of writer Meyer Levin, who immediately saw the potential of the diary to tell an unadulterated account of the Holocaust from a Jewish perspective. He immediately partnered with Otto Frank to find publishers in America, which — coupled with his passionate New York Times review — made it a bestseller in America, the U.K., and Japan.

A “Jewish” play

As Levin expressed interest in taking Anne’s diary from print to stage, Frank and Levin began to clash over their respective visions for the play. While Levin wanted to stay as close as possible to the diary and emphasize aspects of her Jewish identity, Frank wanted to adopt a more generic tone, hoping to portray Anne as a universal symbol of hope and resilience. In a letter to Levin, Frank flatly stated:

Do not make a Jewish play out of it. I always said that Anne’s book is not a war-book. War is the background. It is not a Jewish book either, though Jewish sphere, sentiment and surrounding is the background. I never wanted a Jew writing an introduction for it. It is (at least here) read and understood more by Gentiles than in Jewish circles… So do not make a Jewish play out of it.

Levin rejected this idea, arguing that:

To take out “Jewish suffering” and to put in “all people suffer” is to equalize the Holocaust with any kind of disaster. If you do this, you unhook the search for meaning, you unhook the wrong to the Jews. Then you go on over the years with statements like, “There weren’t six million. There were four million. There were two million. There were a lot of Russians and Poles who were killed in the camps. So the Jews are just exaggerating.”

Eventually, Frank opted to work with a pair of American screenwriters who had already achieved success on Broadway: Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett.

Levin promptly sued Frank for this decision.

He argued that Goodrich and Hackett had stolen his ideas, downplayed discussions of anti-Semitism in the play, and breached an agreement which allowed him to stage his own version of the diary. In 1958, Levin was awarded $50,000 for his charge of plagiarism despite the evidence being ambiguous at best.

Although Levin went too far in terms of engaging in litigation and making public accusations against Frank, Goodrich, and Hackett, he raised a valid point about the dangers of generalizing Anne’s diary. Draft after draft, Goodrich and Hackett were encouraged to broaden the play’s appeal by Otto Frank and director Garson Kanin.

One of the most striking examples of Jewish minimization is when Anne begins to reconcile the horrors of the Holocaust. In her diary, she writes:

Who has inflicted this upon us? Who has made us Jews different from all other people? Who has allowed us to suffer so terribly up till now? It is God that has made us as we are, but it will be God, too, who will raise us up again. If we bear all this suffering and if there are still Jews left, when it is over, then Jews, instead of being doomed, will be held up as an example.

In the play, Anne projects an entirely different message. She says:

We're not the only people that've had to suffer. Right down through the ages there have been people that've had to suffer. Sometimes one race . . . sometimes another.

Despite these deviations from the original text, the play became an international success after its premiere in 1955. In Germany alone, over two million people came to see it. At many performances, viewers left the theater in tears.

In lieu of applause, there was only silence.

Although praise for the play was widespread, it also dealt with its share of criticism. Among the most notable critics was Telford Taylor, who served as the lead counsel for the prosecution of war criminals in the infamous Nuremberg trials.

Taylor asked Goodrich and Hackett why their play had performed so well in Germany, to which they responded that it was a “heartrending work about a lovable young girl and her family”. He told them that people liked the play because it “never pointed an accusing finger at anyone and because it took place in Holland, not Germany”.

It is worth noting that there are many other first-hand accounts of the Holocaust that have been neglected by the public eye, perhaps because they accomplish what Goodrich and Hackett were unable to do in their adaptation. For example, Leon Wells’ lesser-known memoir The Death Brigade tells the story of a Jewish prisoner who is forced to burn the corpses of murdered Jews in the city of Lvov. It is a reminder that audiences must actively seek out the truth for what it often is: ugly and uncomfortable.

While it may take significantly more work — emotionally and intellectually — to find accurate representations of history, the easier path of constructing a more favorable narrative is significantly worse.

Anne Frank put it best:

How can I make it clear to him [Peter van Pels] that what appears easy and attractive will drag him down into the depths, depths where there is no comfort to be found, no friends and no beauty, depths from which it is almost impossible to raise oneself? . . . Laziness may appear attractive, but work gives satisfaction.

Fabulous, and what a subtle reminder of the power that is lost - or siphoned off - when we water down a deeply personal experience to represent a larger audience. It is Black Lives Matter vs All Lives Matter, right? Thanks for the DM that got me here. Great work.

I wish I'd seen this back in August, but at least I'm seeing it now. I finally got around to reading the Diary a couple years ago and I so agree with what you said about it defying expectations. Anne Frank was a gifted writer, "beyond her years," and I wondered how much the original work was edited. That aside, it is very moving, especially moving for it's humility. I did not know about the battle to gain access to the material and I can only be thankful that this book was not co-opted for political purposes. It surprises me that a court would consider anyone but her father, who suffered though the years of imprisonment and death of his entire family, as having "rights" to her story. Though this is a familiar subject, your piece is very enlightening. Thank you.