In 1941, employees at France’s national statistics bureau received a peculiar order. As strange as it may have seemed, the workers quietly obliged. Rivers of documents that usually flowed from filing cabinets to desks slowed to a trickle, and the clack-clack-clack of blocky IBM machines scattered across the office gradually began to die down.

Ever since France had fallen to Nazi Germany in 1940, the government had developed a keen interest in surveying the country’s Jewish population. Collecting this data would allow them to expedite the rounding up and murder of Jews en masse — and coupled with recent advancements in computing — this process could be made alarmingly efficient. However, the French officer in charge of leading this survey found a way to covertly sabotage their plans.

René Carmille, an engineer by training, instructed his workers at the statistics bureau to “slow down as much as possible all activity concerning the Jews”, according to biographer Michel-Louis Lévy. If he was able to stall for long enough, tens of thousands of civilians across France could be saved. If Carmille was outed, he would be killed.

With each passing day, his supervisors grew more and more impatient as they waited for the census to be completed, and each day, Carmille invented new excuses to explain why the data had still not been collected. Perhaps France was simply too vast to survey in a reasonable amount of time, or maybe a faulty machine had prevented a person’s religion from being properly recorded. It seemed to be working, but it was only a matter of time before the Germans realized what he had done.

The systems of genocide

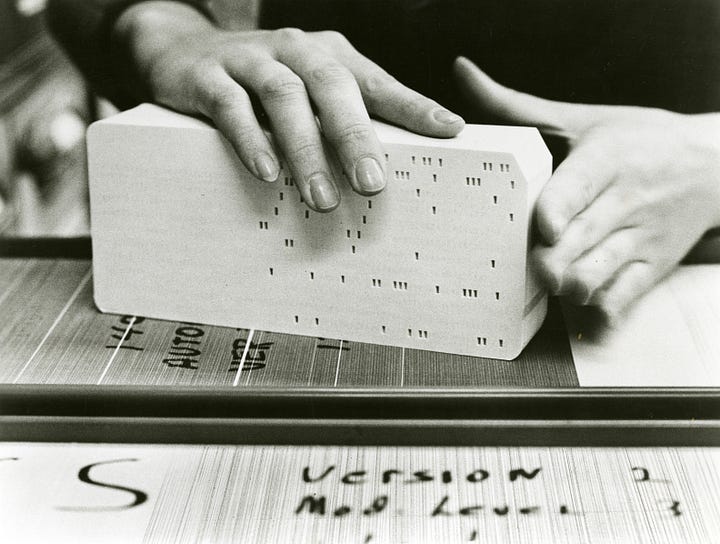

Carmille probably didn’t dream of sabotaging one of the most powerful regimes in the world while he was growing up. He likely envisioned a secure career in academia, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge as a research scientist or educator. After graduating with a degree in engineering from the prestigious École Polytechnique in Paris, he joined the French army, using his mathematics skills to streamline the production of weapons and munitions. It was here where he first stumbled upon punch cards — an innovation key to Germany’s orchestration of the Holocaust.

Invented in the early 1800s, punch cards are pieces of paper that store data by having holes mechanically punched in them. Combined with IBM’s “tabulating machine”, a device that automates the process of aggregating data from thousands of cards, these inventions constituted an enormous technological leap forward that laid the foundation for modern computers as we know them today. In other words, if punch cards were early USB sticks, tabulating machines were the computers that read them.

Tabulating machines were especially useful to Carmille, as his job required him to draw upon countless physical records in order to answer specific questions; for example, how many heavy mortar rounds had been manufactured in the past month? Instead of spending hours tallying up rounds by hand, Carmille could find the answer in a fraction of the time by using a tabulating machine.

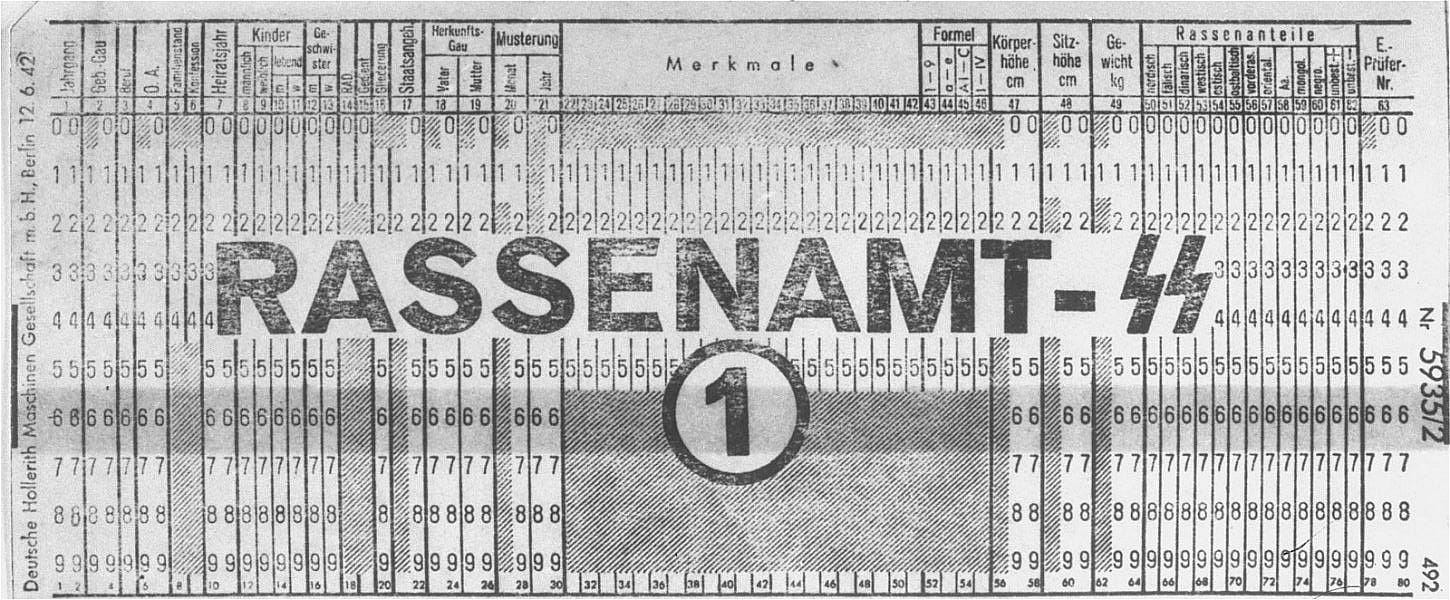

The Nazis immediately saw the potential of this technology to track Jewish citizens at an unprecedented scale, and it was IBM who willingly supplied Germany these machines. IBM’s computers were used in every facet of the Holocaust, from identifying Jews in concentration camps to scheduling the trains that transported them there. In fact, the serial numbers tattooed on prisoners’ arms were originally generated by IBM’s numbering system. To quote historian Edwin Black, author of IBM and the Holocaust:

Without IBM, there would have always been a Holocaust of hundreds of thousands … but it was IBM that helped the Third Reich create the industrial, high-speed, six-million-person Holocaust, metering ghetto residents out to trains, then carefully scheduling those trains to concentration camps for murder and cremation within hours, thus clearing the way for the next shipment of victims — day and night.

The dangers of tabulating machines falling into the wrong hands were clear. However, as Hitler’s grasp widened to France, Carmille again looked to these systems for help — this time, to discreetly assemble a list of demobilized soldiers that could be quickly activated if the government decided to rebel against German occupation. Carmille needed to gather details about millions of citizens, including their ages, locations, and occupations. To accomplish this without alerting his higher-ups, he disguised this massive operation as simply a routine census.

Carmille’s plan miraculously flew undetected for months. In the summer of 1941, government officials put out a bid for the completion of a Jewish-specific census. Carmille saw this as another opportunity for sabotage. If another statistics service took the lead, the results could be catastrophic for Jews, especially if it was headed by a Nazi sympathizer. In a letter to Xavier Vallat, the Commissioner-General for Jewish Questions, Carmille wrote:

In the event that the model of the Jewish census is not definitively established, I am at your disposal to gather all the useful information on the Jews and ultimately to be enlightened exactly on the Jewish problem.

Vallat was convinced. Around Christmas, Carmille’s statistics department was selected for the job. For decades, Carmille had spent his life trying to serve the French government to the best of his ability, meticulously reshaping the country’s slow, antiquated systems into an efficient, well-oiled machine. Now, his objective was to throw a wrench into the cogs that he’d laid; to implode a behemoth that he himself had crafted. Failure was not an option, but it was the solution.

Over three hundred thousand lives depended on it.

The first ethical hacker

Thirty-one questions were included in the French census form of 1941, but one in particular stood out. The eleventh question bluntly asked citizens: “Are you of the Jewish race?”

While the government waited for Carmille to compile their responses into an easily accessible database of punch cards, police relied on handwritten records to persecute Jews in the meantime. In what was the largest French deportation of Jews during the Holocaust, 13,000 people were arrested and confined in the Vélodrome d'Hiver sports arena, roughly half a year after Carmille had been chosen to lead the census.

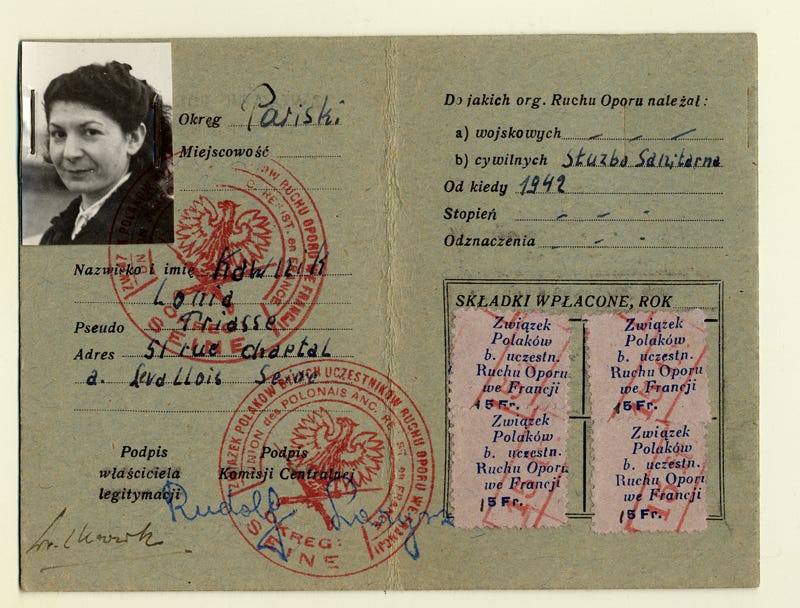

Carmille did everything he could to prevent the census from being completed on time. He ordered his team to slow down, intentionally misspelled names of Jewish citizens, and even reprogrammed his own machines to omit the answer to the eleventh question. According to his son Robert Carmille, who worked with him on the census, “we never punched column 11”. This defiant act earned him the title of the first ethical hacker. Beyond his efforts to delay the census, Carmille also helped over 20,000 Jews evade capture by supplying them with the identity cards of the deceased.

Unfortunately, Carmille couldn’t resist the mounting pressures of the government forever. He accepted requests to recruit people for forced labor in Germany, but in spite of his periodic compliance, German officials eventually grew wise to his role in the resistance. In 1944, Carmille was interrogated and tortured at Montluc Prison in Lyon for two days. He was subsequently sent to the Dachau concentration camp. Carmille passed away early the next year. During his imprisonment at Montluc, he composed a sonnet for his wife:

To my wife,

Thirty years have passed since our marriage.

The roses of love did not want to wither, and their golden petals have always dominated the languid calm sense of the wind of the storm.

We have spent all the time of this age in a world exploding into dislocated debris, where fury summoned by Satan showed in its ugliness what human anger is.

The great love of ours is also the redeemer of human madness.

The hope of our hearts has remained strong among all those who pass.

Although Carmille died before the war ended, the impact of his dissent lived on. In most countries occupied by Nazi Germany, such as Poland, the Netherlands, Greece, and Estonia, more than eight out of every ten Jews in each territory were deported and killed. In France, this number was fewer than three out of ten.

Though this difference cannot solely be ascribed to Carmille, it is likely that his sacrifice saved the lives of thousands of Jews. His commitment demonstrates that resistance need not always be glamorous, and that power need not always compromise one’s morals. It is true that Carmille was a brilliant engineer, but he will be remembered first as a selfless humanitarian.

View our sources for this piece here.

Interesting. I think there were a great many people in France who helped gum up the works of the German occupation. I read in Gerturde Stein's Wars I Have Seen an anecdote about a French Jewish woman who had to register and when she went to the office the government clerk simply said something like, "I did not send for you," and so she left. I wish I could remember exactly how this conversation went but the point of it was he had no interest in doing the Nazi's dirty work and Gertrude Stein makes the claim that there were many people in official positions who had no respect for the German occupiers though they could not openly rebel against them. Stein was Jewish and she stayed along with Alice B. Toklas in Vichy France through the war. Ironically she was friends with Bernard Fey who was a major Nazi collaborator and government official who at the same time protected her. I think the history of France during this period is very interesting in the way they played both sides and managed to keep their country more or less intact.