Several months ago, millions of students across the country celebrated a massive achievement: being accepted to college.

Universities promise broadened career opportunities, more academic freedom, and above all, an unforgettable once-in-a-lifetime experience. Now that the semester is starting, over half of these students will be forced to bear thousands of dollars in debt. By graduation, three out of ten will have dropped out because tuition was too high to continue paying.

Colleges didn’t always impose these financial burdens on students.

Sixty years ago, the average cost of attendance for a public four-year institution like Penn State was only $8,500, adjusting for inflation. For a private four-year institution like Dartmouth, the average cost was about $16,500. These figures have roughly tripled, now $21,000 and $47,000 respectively1.

If we compare these costs to the average family income over the same period, we find that the cost of attending college has grown faster than family income by a factor of eight.

It is clear why most Americans today believe that obtaining an undergraduate degree isn’t worth the cost2. What is less clear is how we ended up here, and what should be done to fix it.

How college became so expensive

The price of higher education is usually justified by some combination of the following: reduced state funding for public institutions, the rising cost of hiring qualified professors, and increased spending on administrative staff, among other factors.

However, these explanations can be inaccurate and do not address the issue at its core.

For example, tuition at public colleges still rose during years when state funding increased. If we blame increased spending on administrative staff, we then raise the question of why American colleges allocate so much of their budget to non-instructional staff in comparison to countries like Finland or Germany. Lastly, if we fault the rising cost of hiring professors, we must ask why the path to becoming a professor is so expensive to begin with.

The bottom line is that there is no federal law that limits the tuition a university can charge.

Unlike several European countries, which offer tuition-free college to EU/EEA citizens, both public and private institutions in the U.S. are allowed to set tuition freely. This means that if a state chooses to cut funding to a university — perhaps to encourage it to reduce its costs — the university can simply raise tuition to make up for the loss.

This effect is what initially caused the tuition hikes of the 1970s.

Consider the City University of New York. Until the city faced an economic crisis in 1975, CUNY was largely tuition-free. To save New York from bankruptcy, the mayor enacted several measures to save money, which included ending CUNY’s tuition-free policy.

The University of California met a similar fate under the governorship of Ronald Reagan, who called for the end of tuition-free policies across the state. Students received their first annual tuition fee in 1970, which is odd given that state funding increased during Reagan’s time as governor. However, his anti-UC rhetoric and campaign promise to slash education spending were enough to persuade the University of California to start charging its students.

Over the next several decades, tuition at both public and private universities skyrocketed. By the turn of the century, students were being charged multiple times what their parents would have paid to receive the same education.

Because government funding for universities has fluctuated over time, it is clear that periodic budget cuts are not solely responsible for rising tuition.

The other problem is that there are few economic incentives for colleges to reduce tuition at all.

The best example of this can be found during the Great Recession of 2007-09. In a period where several million Americans fell into poverty, the number of undergraduates increased by 16%. Given that the government had just raised the borrowing limit on student loans, colleges found that they could simply charge students more instead of cutting back on spending. As a result, the average tuition at public universities increased by 19%3.

The economic protection that universities possess can be attributed to the undisputed value of a bachelor’s degree. Those who hold bachelor’s degrees are half as likely to be unemployed as those who do not. For many, attending college is less of a choice and more of a necessary step in building a stable career. This means that — recession or not — universities will find themselves with a vast pool of applicants ready to pay them tuition.

Without pressure from consumers to drive down costs or a federal limit on tuition, it is clear why college in America is as expensive as it is today.

College in Europe vs. America

If tuition seems steep now, consider the astronomical cost of attending college in forty or fifty years. It is in the nation’s best interest to find ways of reducing the cost of college, as burdensome debt harms not only individuals but the economy as a whole. Comparing the American and European higher education systems may provide some insight as to what should be changed here.

Take the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Copenhagen, for example. Both institutions are public, have roughly 30,000 students, and employ a similar number of people. However, an in-state student at Pitt pays roughly $20,000 in tuition each year. For a Danish student at the University of Copenhagen, tuition is non-existent.

To see why, we can examine each university’s revenues and expenditures4.

The University of Copenhagen’s main source of revenue is government subsidies, with only a small percentage coming from the tuition it charges international students. On the other hand, tuition comprises almost a quarter of Pitt’s revenue. The remainder comes mostly from research grants, contracts, and endowments — with state appropriations only accounting for a minuscule 8%.

Because state funding is insufficient, Pitt recently decided to raise tuition to cover its growing budget5. In-state students can expect to pay an extra $196 per semester, while out-of-state students will be paying an extra $1,270. Interestingly, Pitt has opted to increase its budget by almost half a billion dollars instead of attempting to cut costs.

Last year, the university spent a staggering $2.6 billion — almost double what the University of Copenhagen spent. For both universities, the majority of these expenditures went to compensating employees — with facilities, rent, and other business expenses making up the rest.

The finances of these institutions demonstrate two distinct scenarios: what happens when spending is kept in check and what happens when it is not. Until tuition caps are enforced by the state, solutions like expanded student loans will only fix the symptoms of runaway spending.

Reducing the cost of college

Even if the government wanted to, imposing a federal limit on tuition would be unconstitutional. However, there are other practical methods of reducing the financial burden of college on students.

The first method is to make student loans more affordable. The Biden administration’s SAVE plan will help accomplish this — it is the most affordable loan repayment plan to date. The plan will forgive debt after a certain period and prevent interest from building up, as long as the student makes payments on time.

On average, the plan will reduce a borrower’s payments by 40%6. Every dollar saved on student loans can instead be spent elsewhere, thus boosting borrowers’ standard of living as well as the economy.

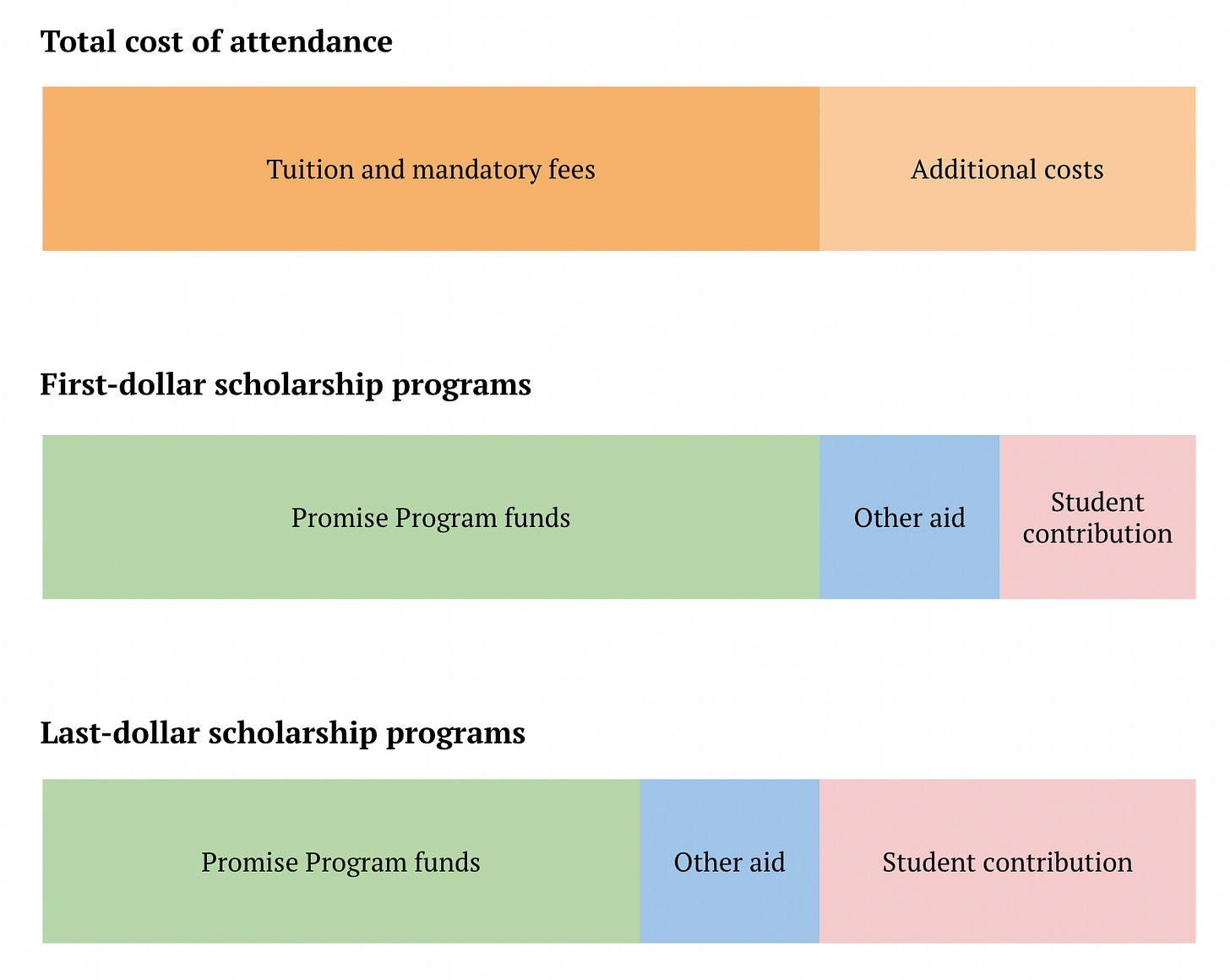

The second method is to have the government or local organizations pay for students’ tuition with no expectation of repayment. This has taken shape in the form of “Promise Programs”, which have achieved success in multiple cities and states. Promise Programs mostly fall into two categories: first-dollar and last-dollar.

First-dollar programs fully cover tuition, meaning that a student can use additional financial aid to pay for other expenses. The Kalamazoo Promise Program in Michigan has employed this strategy, helping over 3,300 students graduate from college. If implemented on the federal level, a first-dollar tuition-free program would cost over $59 billion a year7.

On the other hand, last-dollar programs provide funds to students after other financial aid has been awarded. These programs have drawn criticism for disproportionately benefitting middle and high-income students. This is because — for lower-income students — a significant part of tuition is already covered by aid. Therefore, lower-income students are left with less Promise Program funding to cover costs.

This issue of unfair wealth redistribution was highlighted by Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman in 1980, who was critical of public education in general8. He pointed out that programs that subsidize higher education tend to benefit middle and upper-class students, even though people of all classes pay taxes. Because of this, Promise Programs and public universities must ensure that lower and middle-income students receive more financial assistance than their higher-income peers.

Although it may be possible to have a free higher education system, it will require immense coordination on the local, state, and federal levels. Ultimately, it is up to the next generation of students to make sure that anyone who wants a college education can afford it, regardless of their financial situation.

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_330.10.asp?current=yes

https://thehill.com/blogs/blog-briefing-room/3928015-majority-of-americans-dont-think-college-degree-is-worth-cost-poll/#:~:text=The%20poll%20from%20the%20Wall,said%20it%20is%20worth%20it.

https://www.goacta.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Cost-of-Excess-FINAL-Full-Report.pdf

https://www.controller.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/AFS-FY-2022-FINAL.pdf, https://om.ku.dk/tal-og-fakta/aarsrapport/annual_report_2022.pdf

https://pittnews.com/article/181675/top-stories/new-pitt-budget-includes-increases-in-tuition-operating-costs/#:~:text=The%20committees%20announced%20tuition%20increases,increased%20at%20Pitt's%20regional%20campuses.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/08/22/fact-sheet-the-biden-harris-administration-launches-the-save-plan-the-most-affordable-student-loan-repayment-plan-ever-to-lower-monthly-payments-for-millions-of-borrowers/

https://educationdata.org/how-much-would-free-college-cost

Free to Choose 1980: What’s Wrong with Our Schools?

I was aware of the problem but I was not aware of how it came about. Thanks for such a clear explanation of how we arrived at the ridiculous cost of getting a college degree in the USA.